Devious solutions for those who hate grading

From an expert on the subject

Grading

If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a million times. I love teaching; I hate grading. Over the years, I have devised ways to pare down the task or eliminate it altogether. “Devise” is the perfect word choice, since many of these are actually quite devious. But at this point, seven years into retirement, what can they do to me?

The central problem is that in my courses, students do not take the kinds of tests where they get a meaningful numerical score. They write papers, create multimedia projects, and produce reflective journals and portfolios. When I give the rare exam, it’s essay, not short-answer, true/false, or multiple choice tests.

Devious solution #1. When the University started using + and - grades, I tried just incorporating them into my existing grading scheme. The result was that every student who got a B+ or C+ came knocking on my door for a few more points so they get a higher letter grade. This including the ones who would email me ON CHRISTMAS EVE to lobby for a high grade. (This is one reason teachers hate grading.) So I stopped giving plus grades, until I figured out how to use them.

Devious solution #2. I give letter grades based on the quality of the work and use the pluses and minuses to indicate effort or engagement. In courses based on a single final project, such as our senior capstone, the letter grade is based solely on the quality of the final product. Drafts are only graded complete, complete/late, or incomplete. A student who writes an outstanding paper but does not meet the expectations for class participation, peer editing, or on-time drafts gets an A-. The student who writes a very good paper and exceeds the engagement expectations gets a B+. Only in extremely egregious instances have I lowered a letter grade — at most, one or two students per semester.

Devious solution #3. This is a variation on #2, used only in courses with a very low credit value. I developed this for a 1-credit seminar offered in a living-learning program program, where most of the student work was either attending guest speakers or participating in active learning such as service projects or field trips. All the students got A’s, with the +/- grades applied as in Devious Solution #2. To earn an A+, a student needed to demonstrate unusual engagement with the program in any of a variety of ways.

The grading scheme was announced at the beginning of the semester. In addition to the final grade, they got a letter of evaluation from me explaining what they did (or didn’t do), and I met with each student who got a minus to discuss whether or not they should continue in the four-semester program. I could not drop a student, but this conversation assured them that I welcomed their continued presence and that the grading system would continue. Some left the program; the rest stayed and never got a minus again.

There were two unexpected outcomes from this solution. First, the evaluations formed the basis for letters of recommendation for many of these students for years after they graduated. Second, by the third semester in the program, most of the students were going “above and beyond” and earning A+ grades.

Devious solution #4. This is the most devious solution of all. In one project-based course, my goal was for students to learn and practice new research and presentation skills in a fail-safe environment. An honest attempt, complete and on-time, is the goal. For this class, I developed a grading contract which was signed by every student and myself. The contract basically said that if they completed every assignment on time, had no more than three unexcused absences, and posted weekly progress reports, they were guaranteed a B in the course. To earn an A, they needed to satisfy the B requirements and submit an outstanding final project. So far, so good, in four semesters using this system.

As I said at the beginning, I hate grading. But I love giving feedback, and coaching students over the course of a semester-long project. Traditional grading did not give me the time to offer comments, or encourage students to seek feedback or improve their work through multiple drafts.

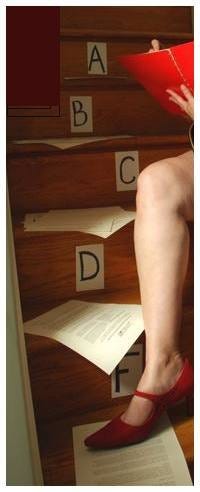

If all else fails, there’s always the staircase method. Red stilettos optional.